This Christmas I got a Sphero Mini robot, a little plastic ball made by a company that started designing rolling robots at a very opportune time for some choice Star Wars merchandising deals. It is controlled remotely via bluetooth, with most of the computation being done on the controlling device. The robot is mostly only responsible for sensors, bluetooth communication, and some basic tasks, like staying upright.

A Sphero moves sort of like a hamster in a hamster ball. The robot itself sits in a spherical shell, like the hamster’s ball. It moves forward by turning the spherical shell with wheels that rest against it. The robot inside the shell is weighted like a Weeble such that it will normally sit upright. The toy is programmed so that it will try to stay upright as the shell rotates around it. If it starts tipping over, the motor will generally turn off automatically until the robot sits upright.

It can be programmed via a stripped down javascript interface .1 I thought I might be able to make a halfway decent toy for my cat to play with while we’re at work. I decided to start with a program that would just go straight until it hit something, turn around in a random direction, and repeat.

That was a lot easier said than done. There is a “collision detection” function, but unfortunately, it rarely detects collisions when they happen. Most of the time, the robot will hit a wall and just keep going into it, oblivious to the collision. Here’s a sad video of that happening:

That video shows typical behavior, running code that is mostly copied straight out of the documentation. The robot will hit a wall and just keep going, completely oblivious to the fact that it hit a wall.

Since I couldn’t find a way to modify the way collisions were detected, I had to come up with a way to do it myself.

The key thing I noticed was that the robot rocked back and forth when stuck

.2

I collected a stream of data from the robot while it was moving normally and while it was stuck.

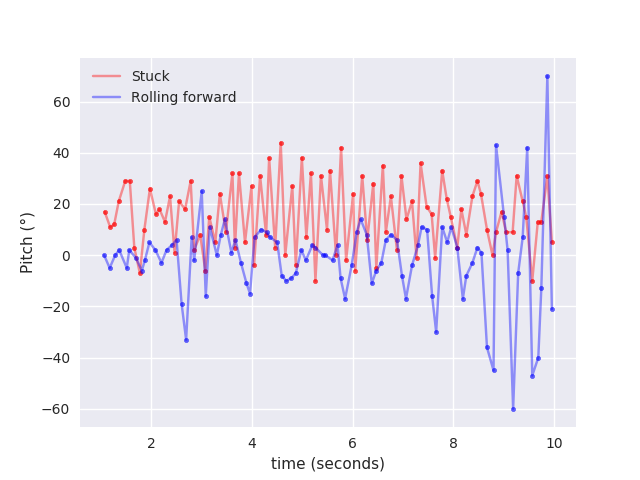

I first looked at the pitch,the angle the robot makes with the horizontal along the direction of its travel.

You can see a comparison of the pitch while rolling and while stuck in the figure below.

You can clearly see the oscillation in the plot that you can see in the video.

However, it might be hard to detect that reliably.

The robot does the same thing while rolling, rocking back and forth, just not quite as fast and consistently.

You can clearly see the oscillation in the plot that you can see in the video.

However, it might be hard to detect that reliably.

The robot does the same thing while rolling, rocking back and forth, just not quite as fast and consistently.

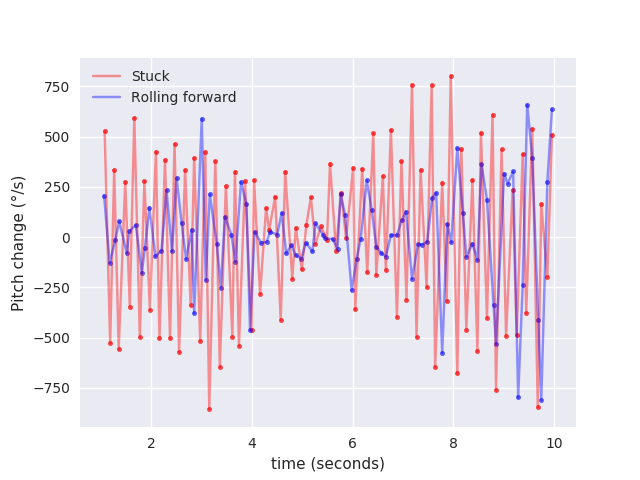

Instead, I looked at the rotational velocity of the robot - i.e. the first derivative of the pitch.3

This was more useful because the amplitude of oscillation was much much greater when stuck than when rolling normally.

Looking at the plot of the rotational velocity of the pitch, as seen in the figure below, we can also see that the frequency of oscillation when stuck is quite high.

The robot is constantly rotating in some direction when stuck.

Meanwhile, when moving, the robot’s rotational velocity generally hovers around zero, apart from some brief periods of movement.

The robot is constantly rotating in some direction when stuck.

Meanwhile, when moving, the robot’s rotational velocity generally hovers around zero, apart from some brief periods of movement.

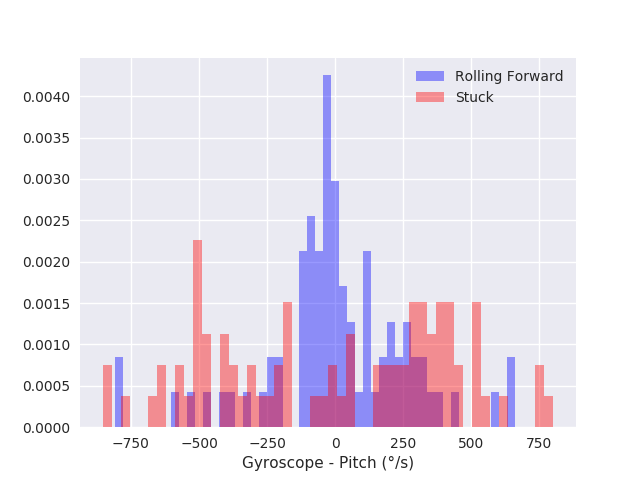

If we look at a histogram of that data, as seen in the figure below, the difference is clear.

When the ball is rolling, the rotational velocity is concentrated around zero.

Meanwhile, the stuck version has a much wider distribution of rotational velocities, and is rather bimodal.

When the ball is rolling, the rotational velocity is concentrated around zero.

Meanwhile, the stuck version has a much wider distribution of rotational velocities, and is rather bimodal.

I figured I could capture this behavior by looking at the standard deviation of the rotational velocity. This is a measure of how “spread out” the histogram of the data is.

I wrote some code that will continuously monitor the standard deviation. If the standard deviation goes above a certain value for a certain time period, it will turn the robot around.

For being pretty rudimentary, it actually works pretty well. I found that I could pretty much eliminate the chance of “false positives” - turning around when the robot is not actually stuck.4 It can take a while for the robot to realize that it’s stuck, but it reliably will eventually.

This program manages to bounce around the room pretty well, but it is far from perfect. I’d like to be able to reduce the amount of time the robot takes to realize that it’s stuck. I’ve tried something that looked at the frequency of the oscillation by looking at the Fourier transform. However, it didn’t seem to complement the standard deviation well, only detecting that the robot was stuck in cases where the standard deviation measure already realized it.

Unfortunately, the Sphero completely failed at my initial goal. My cat has no interest in it, no matter how it is moving around.

1 The interface I’ve been forced to use is the one provided by Sphero Edu. There are other interfaces available for other Sphero robots. However, the Sphero Mini is new, and it looks like no one has released anything else. I personally can’t wait for other options. JavaScript is probably the last language anyone wants to use for numerics. The process of testing code is tedious: write code on your computer in a chrome app with very few coding features, let alone version control, update the version on your phone, connect to the robot, and then discover you forgot to properly match parentheses and start the process over again. I’m especially looking forward to the Go robotics framework. Writing in a compiled language would make finding syntax errors faster, and having a real linear algebra package (or any package for that matter - Sphero Edu doesn’t allow package imports) available would make the code much easier to write.^

2 I’m not entirely sure why this oscillation happens, but I have a guess. A Sphero works sort of like a hamster in a hamster ball, moving by rotating the spherical shell it sits inside. When the robot is hitting a wall, however, the outer shell can’t rotate. Like a hamster trying to run inside a ball that won’t turn, the robot instead moves up the side of the ball. It realizes that its flipping over, and turns off the motor to right itself. Once it has righted itself, it repeats the process, creating the oscillation.

I’m actually quite unsure about this explanation. It might be very wrong. The period of oscillation is about 0.05 seconds. At 20Hz, this is right on the edge of something we’d hear as sound. I doubt the robot would vibrate this fast if the cause is overcompensating while trying to keep itself upright. The robot would have to observe itself falling over and change its what it’s doing too fast for this to be the cause. In defense of this explanation is the observation that the 0.05 second period is about the same as the sampling rate of the data. Because it is interacting with the phone over bluetooth, the sampling rate is about 0.05 seconds. If the oscillation is being caused by flaws in the algorithm for keeping the robot upright, it might have a period of about the one we observe.^

3 This might be a little confusing, since the robot looks like it’s a rolling ball. However, actually it is just the outer shell of the robot that rolls when the robot moves. The actual robot itself inside the shell tends to stay at a pretty constant orientation while the shell rolls.^

4 I found that I could really eliminate the false positives by reading the standard deviation in pre-determined chunks instead of continuously. It often takes much longer than the chunk time - I found 3 seconds worked pretty well - to turn around when stuck. However, the probability of a false positive is much lower than if the standard deviation is continuously monitored, as a false positive standard deviation would have to fit inside a pre-determined chunk, not any 3 second period. ^